Writing about Bioinformatics

This blog started as a way for me to force myself into learning web development and getting used to writing. After getting the "Website saga" posts online I wanted to start writing something a bit closer to where my heart really lies: bioinformatics.

What interested me the most about having this blog is the chance to write technical content in a more conversational tone. In my (very limited) experience, writing a paper is all about showing off the quality and results of your work, and maximizing your results-per-word ratio as much as possible. Because you are writing to the scientific community, there isn't that much room to give the "plain English" introduction, the kind that actually helps people understand what they're about to read.

If you're already an established professional in your field you can pick up any paper and follow along without much trouble. But I'm rarely that person. More often than not, when I read a paper, I'm not just catching up on the latest approaches, I'm also refreshing my understanding of the area. Bioinformatics is so multidisciplinary and broad that I keep finding myself studying for an analysis I've never done before, and probably won't have to do again for a long while.

That's partly my own fault. I get bored quickly, so I've nudged myself into being a generalist rather than a specialist. But the problem, a problem remains. LLMs have gone great lengths to aid this and are now my go-to for getting into new topics, as you can often ask questions about the concepts around what you are reading, which is great for filling in the blanks. LLMs work best for me as a "what to google" tool, as the more niche the field you work on, the less material there is online, so you can't rely on it to give you an accurate answer (so as bioinformaticians we're still screwed).

What better way to start with these writing exercises than to tell you about my brief time working in the microbiome field. My work on alpha diversity metrics started as my undergraduate thesis and ended up becoming my first scientific publication.

By the way, as I kept writing this, I realized that I didn't have to cite every claim I make, and I can cite wikipedia. Blogging is fun!

Microbiome and biodiversity

Pretty much everyone knows what bacteria is. These tiny forms of life are everywhere, and while the average person usually associates them to disease, nowadays most people are aware that not all microorganisms are bad. We use some of them to make beer and bread, others help us keep viruses in check, along with many other things. It is good that they are good, since a particular set of them are inside of you right now and make up about 55% of the cells in your body (That's right, depending on how you measure it, you are more bacteria than human).

Given this incredibly unnerving discovery, scientists around the world decided that it was important to know little bit more about the little fellows, on account of their inevitable proximity to us, and how their distant cousins sometimes go rogue and try to kill us. It turns out they are quite interesting! and from all that effort we learned how to defend ourselves better against them, how to use them for manufacturing, and even copied their homework a bit on how to edit genetic code.

So, how does one study these things? Well, if you start from "I want to study the microbes in the human stomach" the first question you probably want to answer is "How many of them are there, of which kind?". The development of NGS technologies made answering that much easier; we now can take a sample from anywhere, run it through a machine and get the DNA sequences of whatever was on it. Since we spent the last decades painstakingly building a database of the DNA of absolutely everything we stumbled across, we can match the sequences we found on our sample to the database and describe our population.

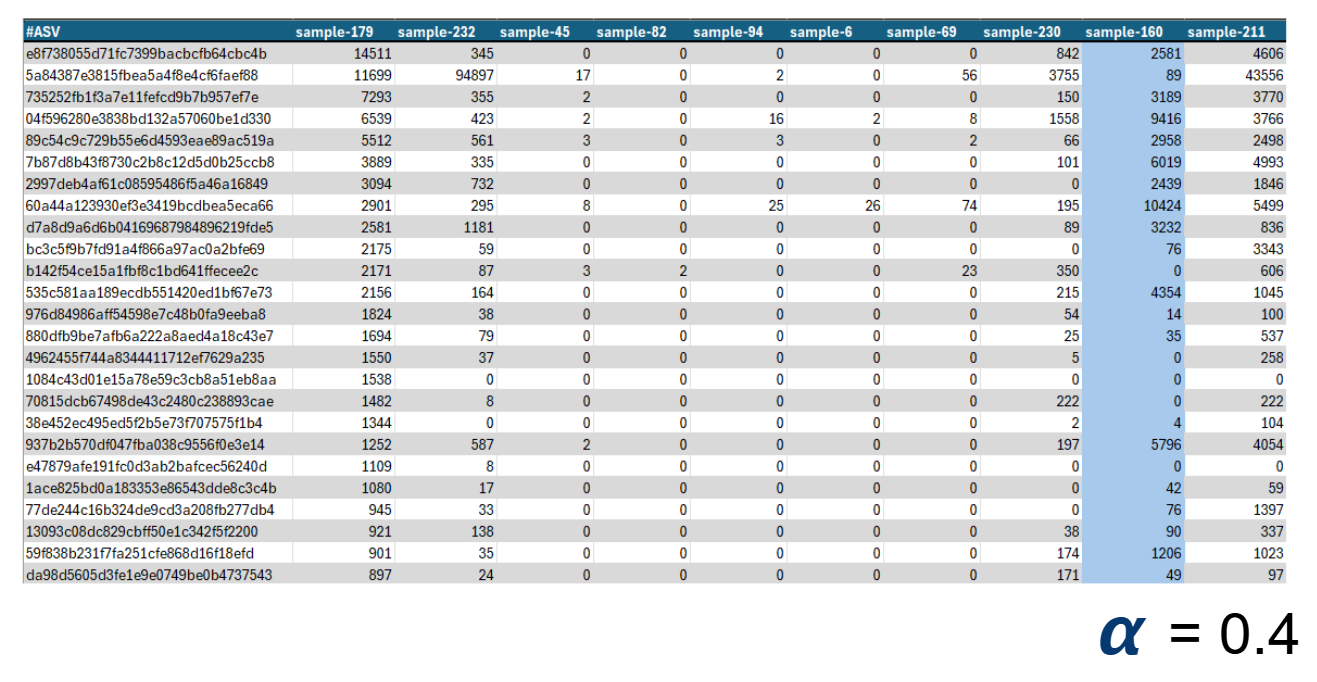

Sounds simple but trust me, it's not. The result is an awful table (called ASV table) with the data for all your samples, which is quite a pain to analyze since It's mostly filled with zeroes. So, we borrowed a few tools from the ecologists, who have been counting how many of each thing they see for years, and started using their biodiversity metrics. These are different mathematical formulas or algorithms that output a single numerical value which tries to describe how diverse a place is. We love these metrics, because instead of having to look at ugly tables, we can check out a single number, see if it moves, and go do something else with our time.

A small section of an ASV table. The numbers are how many times a different ASV (think species) was seen. This one has around 5000 rows. Each column is a sample, which we can summarize to a single number by calculating an Alpha Diversity Metric

With that sorted out we measured the crap out of everything, and biodiversity metrics turned into one of the first things we calculated. Whether you are researching the difference between the gut microbiome of vegans and non-vegans, or the difference between someone's saliva and their armpit, you always report on the biodiversity of your samples first, as a general metric to describe them. After doing this for a few years we identified something pretty neat. The more biodiversity we found (in certain places, like the gut), the healthier the study subjects seemed to be. (This is a very generalized statement, do not take as-is)

The world took this statement as-is, and that made these values VERY important. "More biodiversity = good" was a shortcut for abstracting away the complexities intrinsic to an impossibly complex system, one we didn't and still don't quite understand. From this abstraction, an entire industry was built around the measurement and upkeep of our microbiome, with biodiversity increase becoming the focus of most of the claims. I will leave my thoughts on that for another time.

Alpha diversity metrics and their biggest issue

Biodiversity metrics come in two different flavours, alpha diversity metrics, which describes the diversity of one thing, or beta diversity metrics, which describes the differences between things. Since their invention the issue was resolved and no one has argued about them ever since.

Let's go though and example. Say we are comparing two forests. A simple common-sense approach to measuring the biodiversity would be for us to count how many subjects of each species we saw In each. If we saw 10 different species in Forest A, and only 9 in Forest B, Forest A is more diverse. But what if I spent 5 years living in Forest A and just an hour in Forest B? Or maybe I lived in a cave the whole time I was at A while you scanned Forest B with a high-tech drone. See the problem? How do we account for how much of the forest I visited? This is called the sampling problem, and is only 1 of the many quirks that keep ecologists up at night.

These are the tools we borrowed when we as started to study the microbiome, and these metrics are the ones highly correlated to better health. But note how I keep writing metrics instead of metric. There is more than one way of solving this problem, and here is where the main issue lies.

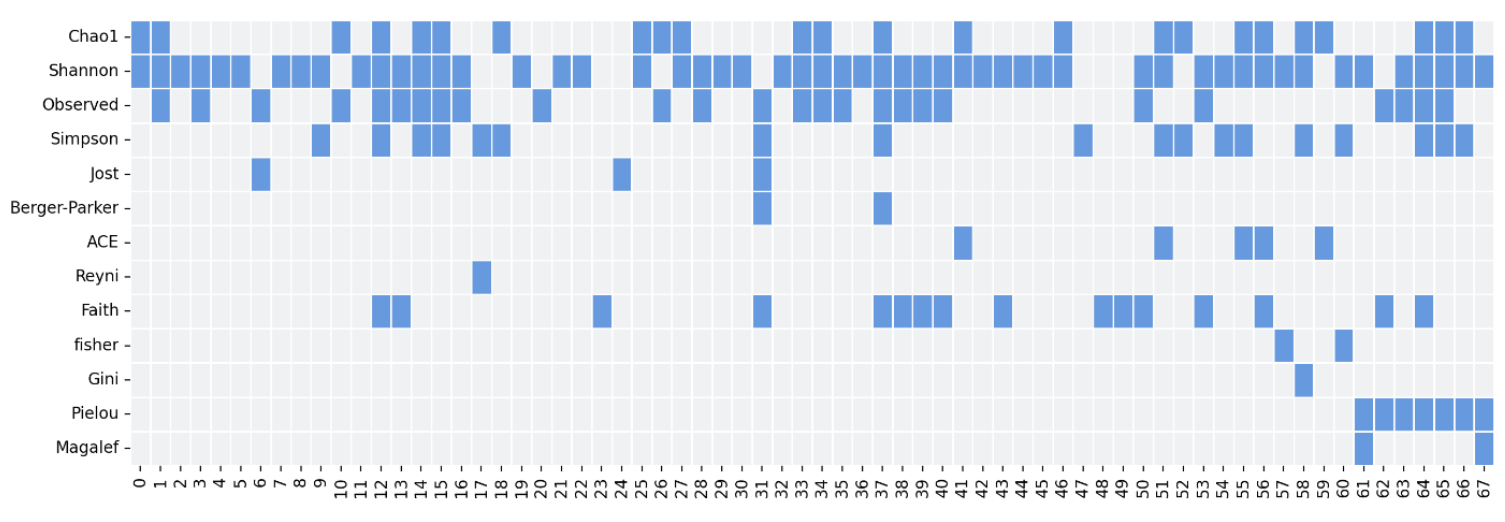

"There as many diversity metrics as there are aspiring ecologists" I heard once (Try to fit that quote in a scientific paper). Just like web developers can't resist the urge of creating new frameworks, ecologists have been inventing new ways to measure diversity for decades. There is some consensus as to which ones to use, but that doesn't take from the fact that in our initial search we identified over 50 metrics, 27 for alpha and 29 for beta, many of which were never used outside their original publication or were only used once. Worse yet, that consensus I mentioned about seemed more dogmatic than we expected, since the choice of metrics on some publications was more arbitrary than we liked.

Take your pick. Table showing which metrics were used by each publication. (Rows are alpha diversity metrics, columns are publications). Not in the table many other cases were they just used one, or weird metrics were only used once (or never), or the two publications that just mentioned "alpha diversity" without explaining what they meant

That's what sparked our research. If you have dozens of ways to measure something… are you sure you are still measuring that one thing? If you are reporting more three metrics, are you stating the same thing thrice? Or are you grouping three different things under the same name? Taken to the extreme, applied case: can you say your product or treatment "increases biodiversity, thus is good for you" if it only increases the diversity according to only one of the metrics? What about two? How many (and which ones) should I use to convince you? Are they all the same?

To summarize our findings, the definition itself is fine. "An alpha diversity metric describes the diversity of a sample" so any formula that applies to any single sample is rightly categorized as such. However, we found 4 subcategories that I believe should be used instead when talking about microbiome diversity. Richness (how different species there are) Evenness (How many of each, how are they distributed) Information (Entropy, the concept from physics) and Phylogenetics (how closely related the different species are).

These 4 very different things were all grouped together under the same term. By having these subcategories defined, communication becomes much clearer, as it directly conveys to everyone which aspect of biodiversity you are measuring and comparing. And more importantly, if you measured "alpha diversity" but haven't calculated at least one value for each category, you are possibly missing out on valuable information about your samples.

That is the gist of it. If you want to read more about our results, this is the link to the full paper.

Why I think it's cool and the importance of abstractions

I find this issue fascinating. Not biodiversity itself, but the themes surrounding it. You may argue that no one should be performing an analysis in a field as complex as human microbiome diversity without a clear, in-depth understanding of what they are measuring and how (and yes, of course you are right). But should that same scientist be equally aware of the principles governing one layer below what they are measuring? What about two layers? What about a few layers above?

Good abstractions are the tools that allow us to work efficiently in the highly specialized work that we live in. Most software developers are aware of this, as these are the terms used to describe the nature of our tools, but it applies every aspect of our world. Here the complexity of the issue is abstracted away under a fantastic simple term like biodiversity. That abstraction is necessary for us to be more efficient in our communication, and is used in media, in classrooms, and even in scientific papers. So who can fault someone new, who comes into the field, reads about it, and assumes we are always talking about the same thing? And yes, the underlying information is still there if you search for it, but how can you tell if you need it or not? How can you tell what is the right level of abstraction for us to be efficient in our work, without risking failing the truth?

The most niche and specific theoretical work in basic sciences, like physics or molecular biology, is connected all the way up to full-scale product manufacturing by layers and layers of abstractions. People will find their calling in every step of the ladder. The question the is: How many layers of abstraction up or down your step should you know about? Who gets to make that call, and how do you keep that communication effective? And how does the new knowledge created by a handful of subject matter experts become available to the hundreds of people who will use it? How much of it should reach the hundreds of thousands of people who will be affected by it indirectly?

I'm inevitably drawn to this subject simply because of the nature of my work. It's the job of a jack-of-all-trades, someone who has to know just enough to be vaguely useful across a baffling number of disciplines. It's a profession that demands you keep up with the breakneck pace of AI, with its weekly, world-altering breakthroughs, while also absorbing twenty years' worth of software development best practices, managing deeply technical AND business-facing teams, and, for good measure, fixing your Linux Bluetooth driver for the hundredth time this year.

It's going to drive me mad one day. That's also why I love it.